The history of truffle (Tuber) collection in Europe dates back to ancient times and is uniquely linked to gastronomy, herbalism and mysticism. Below is an overview of the most important historical milestones and the first written records.

Truffles were already known to the Sumerians and Babylonians between 3000 and 1000 BC, mainly as a natural wonder rather than a culinary ingredient.

The first known written references to truffles are found in ancient Greek and Roman sources:

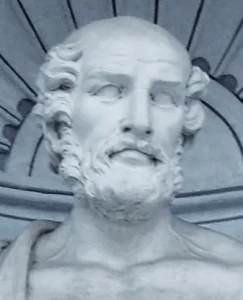

Theophras (371-287 BC)

Theophras a disciple of Aristotle and the father of botany, mentions truffles – wondering how they could grow “without any seeds”. He was the first known author to write scientifically about the world of plants. His monumental work, Historia Plantarum (History of Plants), is the first surviving botanical encyclopaedia, and it is in it that he mentions the truffle, which he describes as a strange, mystical phenomenon.

Theophras did not call the “truffle” by its modern Latin name (Tuber), but wrote about the phenomenon, and probably meant several underground fungal species, his main observations are:

Habitats:

He observed that truffles are more common in a certain type of soil and near woody plants – especially oaks and pines. This was an early recognition of the modern mycorrhizal relationship, even if it did not have a biological explanation.

No visible reproduction:

Surprised to write that it has no seeds, flowers or stems:

‘The majority of plants sprout from seed – truffles seem to be an exception, because there are no seeds or roots.’

From this observation, the truffle was later long considered to be a mineral, not a living thing.

Mystical origin:

He linked the origin of truffles to lightning strikes:

‘The truffle (Tuber) grows underground, and is believed to be born after a lightning strike, as a result of rain and thunder.’

This idea persisted for a long time – it was even invoked in the Renaissance.

The Greek name for the “truffle” was not yet recorded, Theophras probably used the word “hydnon” or “idnon” – a word that later appeared in Latin as tuber, and then in Italian tartufo and French truffe.

Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD)

In his encyclopaedic work Naturalis Historia (Natural History), Pliny the Elder (Gaius Pliny Secundus, 23-79 AD) mentions truffles in several places, mainly as a special, mystical and highly prized edible plant. Although he had no biological knowledge as we understand it today, his descriptions reflect his observations and the beliefs of the time.

Mystical origins – ‘child of thunder’

Pliny, following Theophras, mentions that the truffle is one of nature’s mysterious creatures and does not grow from seed:

‘The truffle grows without root, seed or shoot, by rain and thunder.’

Again, this reflects the idea of the mushroom being born of lightning and rain, which was popularised by the Romans.

Culinary value

Pliny refers in several places to truffles being eaten as a highly prized delicacy. The taste, texture and aroma of the mushrooms were considered to be special. It was mainly found in the meals of the upper classes – a luxury item. The Romans were particularly fond of African and Ligurian truffles.

Medicinal properties and aphrodisiac

According to Pliny, truffles can be a medicine as well as a food. It was believed to improve libido and strengthen the body, although Pliny himself was often sceptical about such claims.

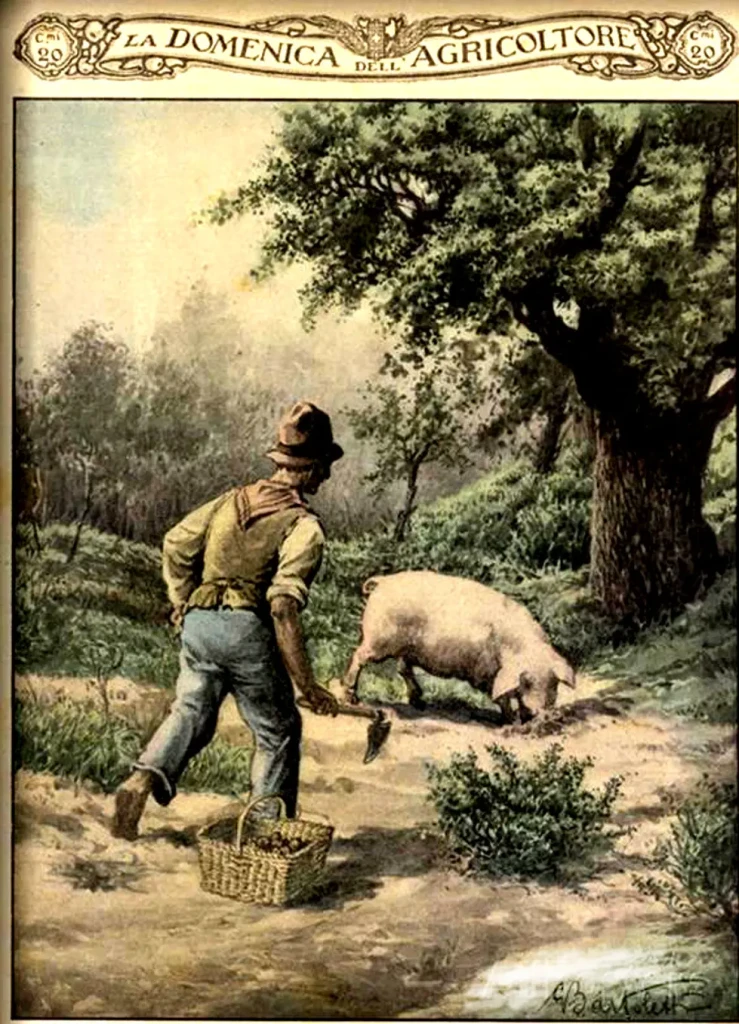

Gathering and hunting

Although he does not specify the exact method of gathering, he does point out that mushrooms generally grow wild and that the knowledge of mushroom hunting was a separate craft in Roman times.

Truffles were considered a natural wonder by the ancient Romans, but in the absence of scientific explanation, they were often associated with magical and mystical properties. Although Pliny was often critical of superstitions, he preferred to maintain the common perception of the truffle.

Juvenalis (1st-2nd century AD)

In his satires, he often mocks the luxury of the Roman elite, and thus the truffle appears as a symbol of luxury.

Satira IV, v. 15-18:

“There is no better hunger than that which is fed by truffles. Mushrooms are worthless, but they must be eaten at a royal price.”

Apicius (end of 1st century AD – beginning of 2nd century AD)

Author or compiler of the collection of recipes “De re coquinaria” (On the Art of Cooking). It is the oldest surviving Roman cookery book.

De re coquinaria, Liber VII, Caput XIII:

‘Crush the warm truffles and sprinkle them with fish sauce, pepper and caraway (concentrated wine), or fry them in the oven with olive oil.’

This is a concrete gastronomic recipe that shows how truffles were used in Roman cuisine – combined with spicy, intense flavours.

Martial (A.D. 40-104)

In his epigrams, the poet repeatedly writes about the splendour of Roman feasts.

Epigrammata, XIV.93:

‘The truffle is a gift of the earth, but not peasant:

It is fit for kings to adorn the table.’

Here again, Martial emphasises social status: truffles are the jewels of royal tables.

Petronius (1st century AD)

In the satirical novel Satyricon, he mentions truffle-like mushrooms in his feast scenes (especially in the famous Cena Trimalchionis).

Satyricon, cap. 70:

‘Golden mushrooms were given as gifts – but they were made of clay.’

The scene is a satire on Roman hospitality, where the falsity of luxury is also on display: the gifts that appeared to be golden truffles were in fact made of clay.