In the Middle Ages, truffles were already known and consumed, but they were not equally widespread or appreciated everywhere. The knowledge was passed down from the ancient Roman Empire, but was often obscured or distorted.

Monasteries, especially Benedictine monasteries, played an important role in preserving knowledge of natural remedies and foods, including the use of mushrooms, including truffles.

Beliefs and mysticism:

Truffles were often attributed to mystical powers because they grow underground and are difficult to find. In the Middle Ages it was often associated with lightning, fertility or demonic powers.

In some places, it was forbidden to take or consume, as it was associated with witchcraft or “satanic practices”.

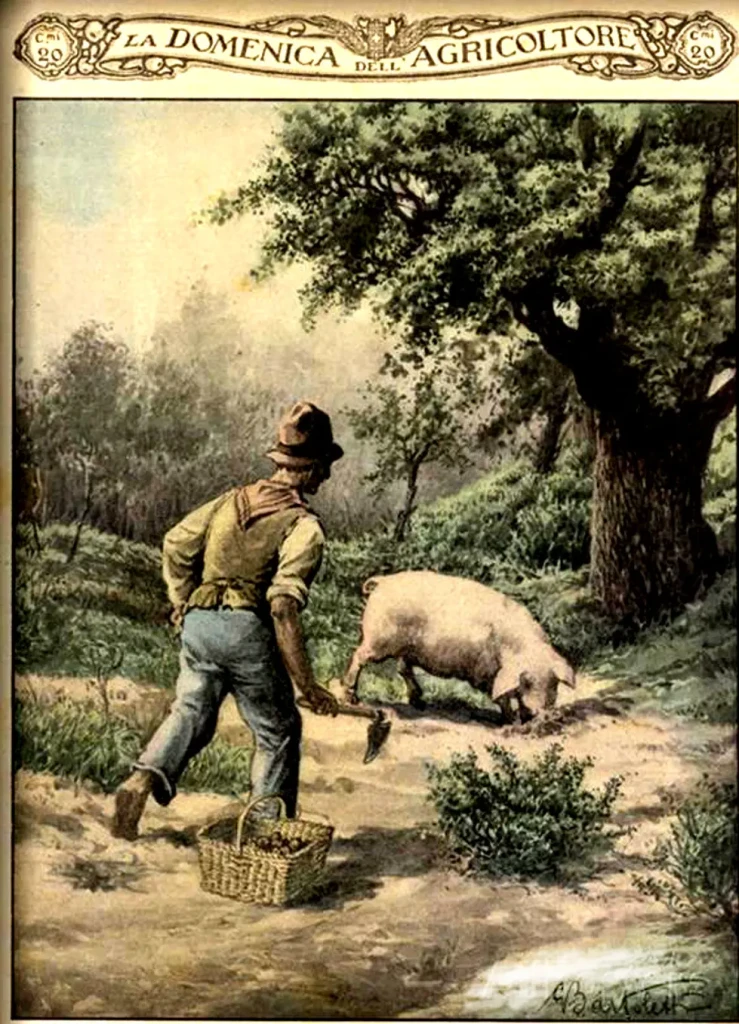

Truffle picking was more common in southern and central Europe (e.g. France, Italy, modern Spain, later southern Germany, Austria), where the climate and soil were favourable. Dogs and pigs were also used to search for truffles in the Middle Ages, mainly in southern Europe.

Pigs naturally sniff out the fungus, especially females, as the smell of the fungus is similar to the pheromone of male pigs. The use of dogs became common later, as they eat less mushrooms than pigs.

Collection was not regulated, but in many places it was the prerogative of the landowners, who could even claim the mushrooms from the peasants in the form of taxes.

North of the Alps, it was collected less frequently, partly for climatic reasons and partly because of cultural differences.

In the Middle Ages, truffles were considered a luxury item in the courts of the nobility, especially from the late Middle Ages (13th-15th centuries). It was often used as a spice and flavouring in meat dishes and pâtés.

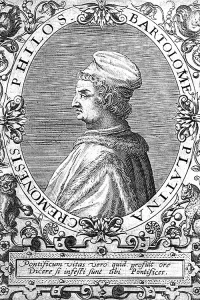

Written recipes are rare, but some contemporary sources (e.g. the 15th century Italian writer Bartolomeo Platina) mention truffles.

Bartolomeo Platina (1465-1481)

Platina, the Papal cook and gastronomic writer, mentions truffles in his first printed cookbook, De honesta voluptate et valetudine (c. 1470-75):

‘…when he recorded that the sows of Notza were without equal in hunting truffles, but they should be muzzled to prevent them from eating the prize.’

This gives us an insight not only into the use of the mushrooms, but also into the methods and practices used when picking them.

Although there is no specific truffle-based dish recipe, Platina does list it in Book 10:

‘truffles’ as the last course in a vegetarian or vegetable dish (for example, after salads, fried pasta, rice, egg and mushroom dishes) . This suggests that truffles were on the menu as a delicacy, at the end of the meal, rather than as a main course.

Platina mainly translated and published Martino da Como’s recipes, often noting when he recommended certain dishes for health or edibility reasons (e.g. certain dishes might be “dangerous”)

For the truffle recipe, no specific health characterisation has been preserved, but only the truffle itself is mentioned as a valuable ingredient, a “delicious” dish.

Early medieval herbaria (herbaria, herbal books)

Medieval herbaria – e.g. the Paris Herbarium (12th c.), Dioscorides’ transplants (e.g. Pliny) – focused mainly on medicinal plants and known botanicals. Fungi with a terrestrial lifestyle, such as truffles, were typically neglected because:

- They were not considered medicinal.

- Their appearance was often neglected by scientific literacy.

Herbaria do not contain detailed, mainly non-culinary, descriptions of truffles. Mushrooms tend to be classified as “militetes” or other categories, but are not prominently featured in either medical or nutritional recipes. These texts focus on plant species, not mycological groups.

Tractatus de herbis (Tacuinum sanitatis, 13th-15th century, northern Italy)

This herbarium (Tractatus de herbis) generally lists hundreds of plants, animals and minerals with medicinal properties – although the specific description of truffles (Tuber) does not appear in all versions. In the Herbarium, the material discussed begins with a qualitative classification (‘hot, cold, dry, moist’) and then continues with typical indications . Although we have not found a specific truffle chapter in this source digitised from the text, the structure would have allowed for its inclusion.

In a manuscript from 1476-1500, which belongs to the tradition of the Tacuinum sanitatis, the phrase ‘tubera id est tartufule’ is used, i.e. ‘truffles, or tartufule’

The Latin original and translation:

‘tubera id est tartufule: Natura: frigida et humida in secundo gradu; …’

‘truffles, that is, tartufule: nature: cold and moist in second degree; …’

This shows that the medieval herbaria already distinguished truffles from other types of fungi and described their warm/characteristic moist properties.

French medieval mentions

In French parlance, truffles were usually considered ‘demonic’ in origin in the Middle Ages, and were even banned by the Inquisition:

‘champignon noir, sous-terrain naissant avec la foudre… la Sainte Inquisition pour l’interdire’

Prince Jean de Berry (1340-1416)

Jean de Berry of Burgundy (Lord of God) was already spreading truffles at the French court at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries:

‘Le duc Jean de Berry (1340) la fit connaître à Charles V puis Charles VI lors de son mariage avec Isabeau de Bavière (1385).’

In addition, the famous medieval pictorial codex Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (1413) also depicts the truffle collection.

The arrival of the first Pope (Clement V – 1309) in Avignon signalled the reconciliation of the Church and the truffle, which from then on never ceased to inspire the clergy, to the point where Saint Anthony was appointed its protector. The Regency period saw the golden age of the truffle, promoted as a royal delicacy, associating luxury and voluptuousness.

Spanish medieval references

Recipes of Al-Andalus (13th c.)

Truffle recipes existed in Spanish-Arabic cuisine as early as the 13th century:

‘aparece en varias elaboraciones de los recetarios andalusíes del XIII, …recetas… “plato de trufas y carne” y “plato de cordero con trufas”.’

This clearly shows that in medieval Islamic Spain, not only were truffle recipes known, but they were also used specifically for meat dishes.

Documents and myths in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries

Although it was suspected by the Church, medical opinions and myths about truffles, such as the “harmful” effects mentioned by Dr Laguna, also appeared later in Spain – this is close to the early modern period.